When the Right Material Isn’t the Right Choice

“Failure is only the opportunity more intelligently to begin again.” wrote Henry Ford in his autobiographical novel, My Life and Work. Learning from our mistakes is small consolation, however, when our instinct was to avoid those mistakes in the first place. Ideally, we learn first from the mistakes of others, then from careful planning and rehearsal, and only as a last resort by bearing the full cost of our own mistakes.

It is this latter category that I have found myself guilty of, and the cost—while modest in physical materials—accounted for a full week of lost production.

The Detour box utilizes several rather small parts for a particular mechanism of my own design. For the initial prototype, I created these out of hard white maple. These parts need to operate smoothly, have low friction, and not fail as a result of wear. I had planned to make the production version of these parts again from hardwood, but allowed myself to be convinced that a more robust material would be to use an engineering thermoplastic – acetal homopolymer – commonly sold by the brand name Delrin.

On paper, Delrin sounds like an ideal material for this part: low friction, high stiffness, and excellent dimensional stability. I ordered a few sheets of 3/16” Delrin from a supplier I found online. Once they arrived, I encountered my first warning sign – the sheets were not completely flat and had a very slight bow to them. I didn’t foresee this as a huge problem, however, as my plan was to hold the sheet down with double-sided tape to a spoilboard before using my Shaper Origin (CNC router) to do the initial shaping.

When routing parts free from a sheet, the ideal cut depth is just barely deeper than the material thickness. Too shallow, and you leave an “onion skin” that needs to be cut/broken and then the parts need to have their profiles cleaned up. Too deep, and you cut through the sheet and into the spoilboard, and likely into the adhesive holding the sheet down. For something like double-sided tape, routing into it can badly gum up the router bit and require cleaning intervention.

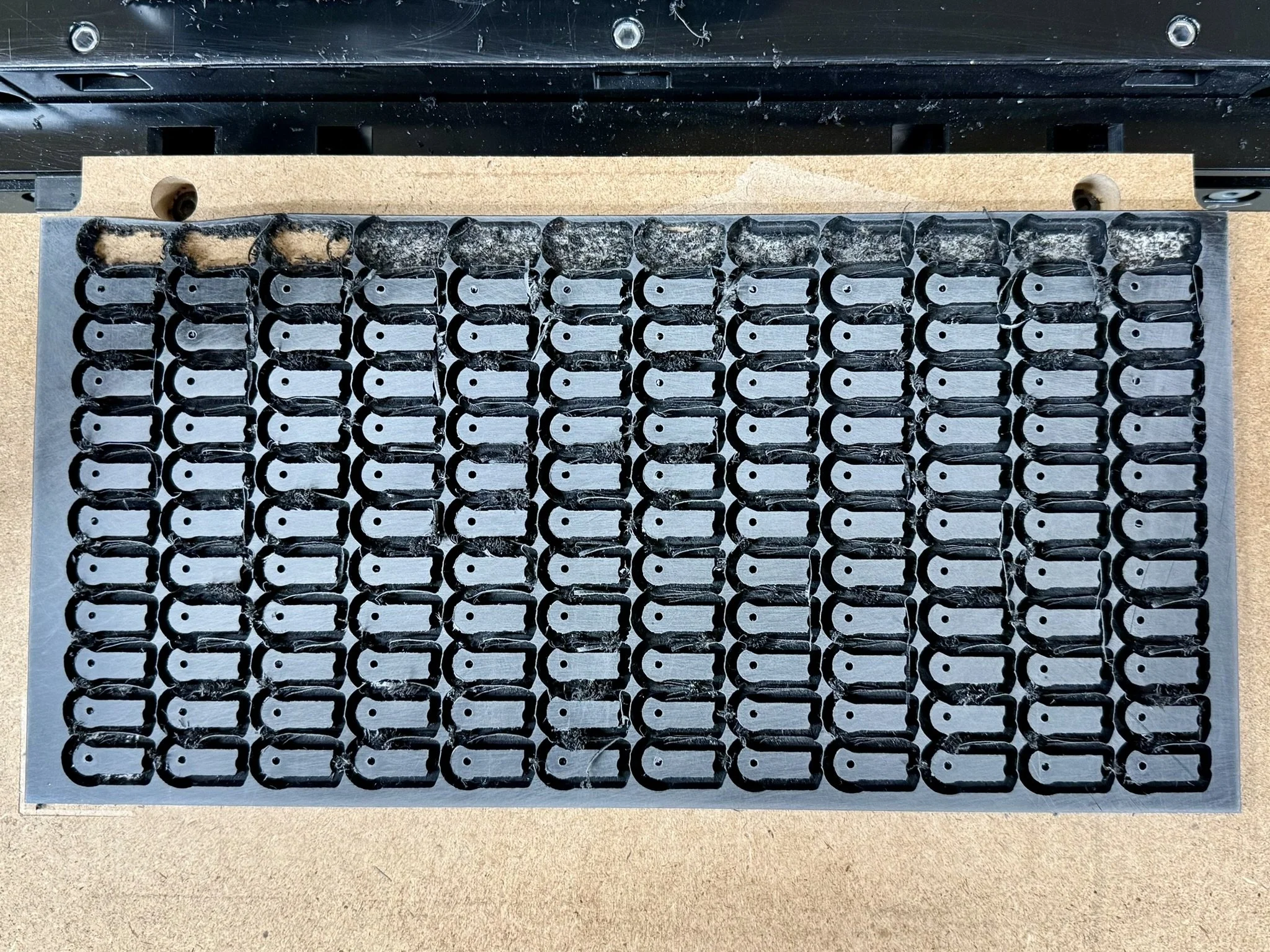

When routing out the parts from the Delrin, I encountered both these problems; in some sections of the sheet the router was leaving an onion skin, and in others it was routing into the double-sided tape. I later realized the cause: the sheet I had was not a consistent thickness. This was already turning into a headache, but I decided to soldier on.

I had produced about 150 of the parts I needed, and almost all of them required some sort of manual clean up to remove onion skin flash and upcut burrs. This is when I discovered another drawback from using Delrin: you can’t sand it to clean up the profile; you need to use a knife. The Delrin may be plastic, but it is also pretty hard, so it doesn’t clean up easily. If you think cutting and scraping the profile of 150 small hard plastic parts doesn’t sound enjoyable, you’d be correct.

After nearly two days of fussing over these parts, I checked one aspect of their fit. They need to swivel easily on a 2mm stainless steel pin, and were all produced with an oversized pivot hole using a helix cut. Unfortunately, all of them were too tight and jammed on the pins instead of spinning freely. Delrin has a tendency to elastically recover when being machined; as a result, all of the holes were not oversized, but undersized and tapered.

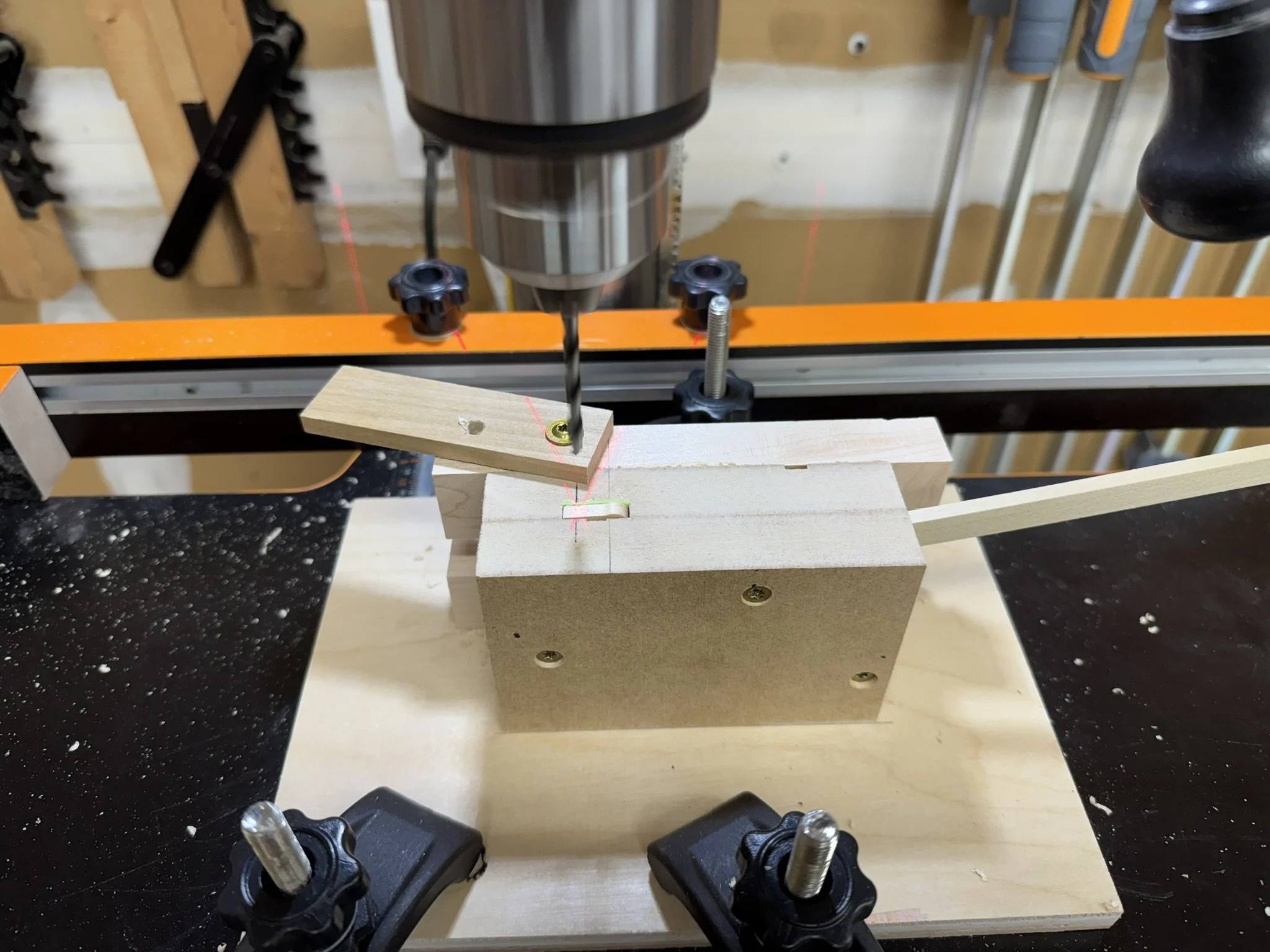

I needed a way to redrill all the holes using a larger oversized bit. The parts were too small to safely hold by hand, so I created a custom jig that could hold the part in exactly the correct position while I drilled out the hole with a 3/32” imperial bit (slightly over 2.38 mm) - which should allow it to spin on the pin. After drilling all these holes, the parts again needed hand detailing to remove burrs around the holes.

Since I seemed to be over the worst of the hurdles, I proceeded on to the next machining stage which was to create a 4mm diameter pocket on the side of the part. This too required a special jig to handle safely and repeatably – I’ve learned that custom jigs are an essential aspect of batch production.

One hundred and fifty small holes later, and I was ready to test the parts in their final configuration. They fit within a small pocket and had to move freely on the pins they mount to. The first one I tried was stiff and rubbed on part of its profile. So did the second one. And the third. Nearly every single one required additional cleanup – shaving off small bits from their profiles to allow them to move smoothly.

At this point I realized that I had fallen victim to the sunk cost fallacy, and would be forever chasing correct operation with these parts. Even if I got them satisfactorily working in my shop, I would have low confidence in them after they went out the door in a working puzzle box. It was time to scrap them and start over again with my initial plan – hard maple.

Because I could reuse my design and jigs, it took me only a day to recreate all the parts (which had taken 5 days of work so far) out of hard maple. The resulting parts worked perfectly and were easy to lightly sand if I needed to tweak the fit on any of them.

I’m glad that I’ve ended up using wood again for the part – there’s something appealing about keeping the mechanism in wood for a wood puzzle. Despite the expectation that this part will never be seen by the solver, it seems more appropriate to keep the puzzle “pure.”

In the end, the lesson was not that Delrin is a bad material—it’s excellent in the right context—but that materials which look ideal on paper don’t always align with the realities of small-batch, high-precision work. The time I lost here wasn’t wasted so much as concentrated: it clarified the limits of my process and reaffirmed choices I had already made for good reasons.

With these parts now remade in hard maple and performing exactly as intended, production is back on track. The experience has reinforced a principle I try to follow whenever possible: when something is meant to be precise, durable, and elegant, simplicity and familiarity often outperform theoretical optimization. The Detour boxes are better for it—and so is the process that’s producing them.